· 9 min read

What's in the NYC city council's public records?

👉

This is a post I wrote for my newsletter, Keys to the City Council, in which I cover NYC City Council legislative activity. In it, I talk about:

- How legislation snakes its way through city council.

- All the records the council generates along the way.

- What you can and can’t find in them.

- How I use AI to sift through it with techniques you can use.

Every bill that makes it to a vote in the NYC city council passes.

(One bill didn’t pass in 2022. Before that, the last time a bill didn’t pass was in the 90s.)

The council holds Stated Meetings twice a month to introduce new legislation and vote on bills, and the outcome of these meetings is determined by the time the agenda is up days in advance on Legistar, the council’s public records system.

Stated Meetings are 90% procedural and 10% performative. Council members use whatever time they get on the floor to tout legislative achievements and explain “nay” votes they cast.

The meetings are predictable, – everything passes! – but the number of bills passed is surprising: the council passes dozens of bills every two weeks, passing over fifty at the last meeting.

Bills take anywhere from months to years to go from introduction to vote. Timelines exceeding one year are not unusual.

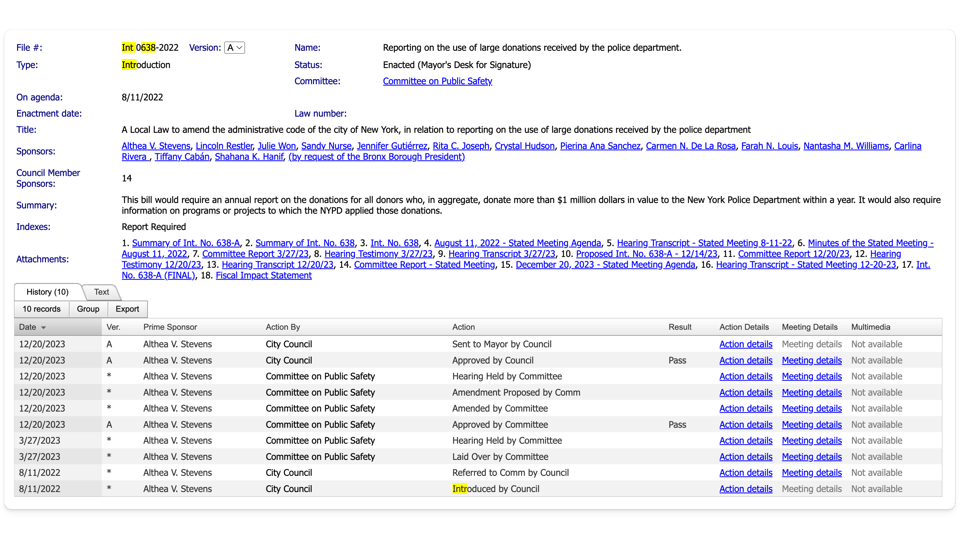

Introduction 638 from the NYPD transparency package passed two weeks ago.

It took 1 year and 4 months to come to a vote.

At some point in 2022, Councilmember Althea Stevens decided to prioritize NYPD transparency and her office worked with the council’s Legislation Division to write the first draft of the law.

(The Legislation Division’s Bill Drafting Manual is an interesting read!)

Then Stevens formally introduced the bill at a Stated Meeting in August 2022, where it was assigned to the Committee on Public Safety.

(Whenever a bill is introduced, it gets assigned to one of 36 committees responsible for deliberating and holding hearings on bills pertinent to them.)

A bill’s public record starts the moment it is introduced. Here is 638’s timeline over 16 months:

- August 2022: the bill was introduced.

- March 2023: a multi-hour hearing was held and the bill was on the agenda.

- December 2023: the bill was revised, brought to the floor, and passed.

There are 18 documents in the public record for Introduction 638 clustered around these three moments. They include every version of the bill, hearing transcripts, written testimonies, and reports with additional context and data.

Here’s what all this looks like on Legistar:

With this data you can:

With this data you can:

- Find out what a bill does by reading its text and summaries.

- Gather context and motivations behind a bill in committee reports.

- Learn what agencies and individuals who testified at hearings think about it.

- Find out how much a piece of legislation will cost the city by reading fiscal reports.

The vast majority of bills never make it to the floor.

Out of 1,281 bills that were introduced in the last two years, only ~20% made it to a vote. Close to 1,000 bills were drafted and then hit a snag somewhere.

Introduction 396 is one such bill. It requires preschools to maintain lead levels in drinking water below some amount determined by the Department of Health (DOH), with a yearly inspection.

Councilmember Robert Holden, the bill’s sponsor, introduced 396 at a Stated Meeting in May 2022. It got assigned to the Committee on Health and then nothing happened: there were no hearings, reports, or votes.

396 seems important, but information beyond the bill’s text isn’t in the public records. I can’t tell you how much of a risk lead poisoning is in our preschools, but a council member’s office thought it might be high enough to address it with legislation.

Even when bills pass, the records don’t tell us the story behind them. The public information on Legistar is sparse and lacks broader context.

But there’s still a lot to discover. The council, like every legislative body in the US, puts out reams of documents that barely anyone reads.

But there’s still a lot to discover. The council, like every legislative body in the US, puts out reams of documents that barely anyone reads.

Surprising details are buried in reports. Here are two from issues one and three of this newsletter:

- From a committee report found here: the city pays service providers so late that they keep themselves afloat with loans, paying an average of $223K annually in interest.

- From a fiscal impact report found here: noise cameras used to detect noise violations cost $35,000 each.

Bills might get revised and change materially from when they are first introduced. This happened with the bike lane bill covered in this first issue of Keys to the City Council:

- The first version enables bike lane improvements fewer than 4 blocks in length without a notice period or community board hearing, on par with other transportation infrastructure.

- The final version of the bill subjects bike lanes of any length to this red tape, unlike other transportation infrastructure.

Exchanges between council members and city agencies reveal new information. For the second issue of Keys to the City Council I poked around a hearing on small business contracts. In it, agencies share how one caterer takes advantage of NYC’s bureaucracy by charging rates ranging from $3/meal to $15/meal to different agencies for the same meals.

As I read documents and build tools and techniques to navigate them – how I spend most of my time on Keys to the City Council – I’m able to find notable details more quickly.

I want to share some of the techniques I use to help me navigate legislative documents and hearings with AI. You can try these out at home using ChatGPT.

I want to share some of the techniques I use to help me navigate legislative documents and hearings with AI. You can try these out at home using ChatGPT.

I pay for ChatGPT ($20/mo) so I get access to GPT-4, a more powerful language model that I use exclusively because GPT-3.5’s performance on these tasks is much worse.

The prompts below use bills found on Legistar and sections of the NYC legal code found on American Legal Publishing.

Here’s the prompt I use to explain what a bill does, with a section to provide context from the legal code if necessary:

Please summarize this NYC bill and explain its implications in a way that a high schooler would understand.

The bill may refer to sections in the NYC legal code. I have provided the bill and relevant sections of the legal code below.

— THE BILL —

Copy and paste the bill text— RELEVANT SECTIONS FROM THE NYC LEGAL CODE —

Copy and paste relevant sections of the legal code

Asking ChatGPT to explain implications “in a way that a high schooler would understand” is a proxy for “keep it simple” that encodes instructions like “don’t go clause by clause and explain it to me like a legal scholar” and “keep the summary high-level and use basic prose”. It works well.

I’ll then have follow-up questions and have a full conversation about the bill. I use questions to verify my understanding, dig into details, and ask ChatGPT to spit out clauses, verbatim, that achieve something in particular.

It’s important to verify ChatGPT’s answer because ChatGPT hallucinates.

Collectively, all this takes me 2-10 minutes where reading and parsing a bill alone might take me 30 minutes or more.

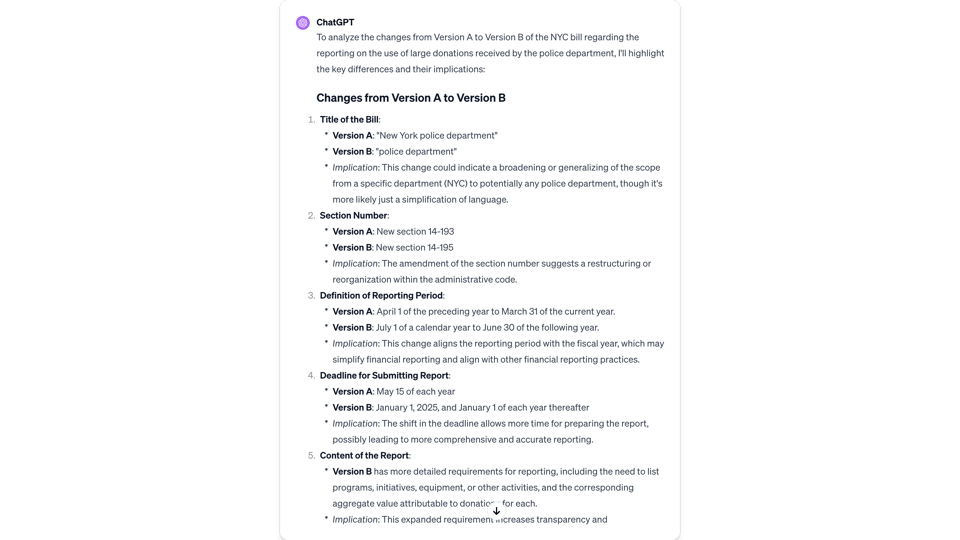

To understand how versions of a bill differ, here is how I prompt ChatGPT:

I will give you two versions of a NYC bill that passed, Version A and Version B. Please tell me what changed from Version A to Version B and what the implications are in a way a high schooler would understand?

— VERSION A —

Copy and paste the text from Version A— VERSION B —

Copy and paste the text from Version B

I used this prompt + followup question to find subtle but material changes in the bike bill covered in the first issue of Keys to the City Council

I also use it to skip revisions that aren’t notable and save time. The screenshot below compares both versions of Introduction 638: the changes are immaterial.

Outside using prompts to analyze bills, I’ve been building custom tools to find interesting information in hearings. This turns out to be a much more challenging task.

Outside using prompts to analyze bills, I’ve been building custom tools to find interesting information in hearings. This turns out to be a much more challenging task.

Part of this is because it’s hard to articulate what “interesting information” even looks like in a hearing. To prompt language models so you get output that you want, you need to be wildly pedantic or use proxies that express your intent well enough, like “explain this to me like I’m a high schooler.”

Saying “tell me surprising facts people said in this hearing” doesn’t work.

The other reason this is hard is because hearings are long, on the order of 30K to 100K messily-transcribed words. Language models struggle to get useful information out of large bodies of text even when your prompt works well on smaller chunks of text.

So I’m hacking on research tools to help me navigate hearings more quickly instead of relying on GPT-4 to give me answers.

In particular, I’d like a page where I can see a video of a hearing on the top and on the bottom:

- Neatly segmented chapters of the hearing: “Roll Call”, “Brooks-Powers expresses concern about NYC’s rat problem in her opening statement”, “An exchange about wheelie bins with DSNY”, etc.

- Each chapter has an associated summary that I can skim, with relevant pull quotes.

- I can expand the transcript in each chapter if I need to skim it.

- I can click on any of these things to automatically seek to a point in a 1-to-4-hour video: a chapter, a pull quote, a single word in the transcript.

Doing this requires creating smaller transcript chunks for GPT-4 to digest, multiple steps involving different prompts, and a lot of manual evaluation to test and improve the quality of chapters, summaries, and pull quotes.

I share more about this work on Twitter and Threads if you’d like to follow along.

I’m building this tool for Keys to the City Council. I think it could be useful to reporters and government affairs folks. If you or someone you know would like to chat about it, please send me a message!

Going forward, I’m going to focus Keys to the City Council on bills and records that are interesting but not widely covered: new legislation, important nuances in bills and revisions, and context buried in hearings and reports.

Going forward, I’m going to focus Keys to the City Council on bills and records that are interesting but not widely covered: new legislation, important nuances in bills and revisions, and context buried in hearings and reports.

In some cases I’ll add to mainstream stories – for example, sharing multiple major bills in the NYPD transparency package that were overshadowed by the one that Adams is likely to veto. Those bills, alone, should generate significant, new public information about NYPD’s operations in the next 12-24 months.

I’m also going to match the council’s cadence and write the newsletter every two weeks when the council votes. I’ll play around with same format I used in issue 1 and issue 3, sharing new legislation along with details.

I won’t cover major stories like the budget cuts in issue 2. The cuts were covered everywhere, and stories like it require context absent from public records that I don’t have, that journalists gather, think, and write about all day.

It was fun to write that issue, but it’s not in my wheelhouse and it took effort and time away from what I want do: poke my (AI-enabled) nose into public records and share what I find.